Earth Blocks: From Mud to Wildfire-Resilient Homes

Wildfires are destructive and hazardous for communities worldwide. Research indicates the potential for wildfire destruction is increasing on a broad-scale, which is why it is necessary to take action now! According to a model built by the nonprofit First Street Foundation, nearly 80 million properties in the United States stand a significant chance of exposure to fire. Read below to learn more about the many ways to mitigate risk and improve your community, including:

- Defensible Space Zones

- Vegetation Management

- Home Hardening Solutions

- Application of long-term fire retardants

Original article written by Miriam Aczel, Postdoctoral Scholar, EcoBlock, California Institute for Energy & Environment (CIEE)

As California experiences widespread drought, the threat of wildfires is growing. Increased fire danger has also meant an increase in the cost of insurance premiums for homeowners as well as the potential that insurance companies will cancel policies for risk-prone properties. Although the state has currently issued a moratorium on policy cancellations during a wildfire crisis, this is just a temporary fix as it is set to expire at the end of 2022. With projected climate change increasing drought conditions, the likelihood of wildfires will likely increase as well.

Protecting Vulnerable Communities: Enhancing Wildfire Resilience

As the threat of wildfires looms across the Golden State, rising housing prices in urban areas are pushing people further into wooded areas. The most vulnerable populations may live in the riskiest environments, as they may lack the resources to relocate.

Making communities more resilient in the face of wildfire threats requires controlling burns and clearing brush, developing evacuation plans, increasing the budget for fire departments, and educating residents and businesses about hardening their properties against potential fire danger.

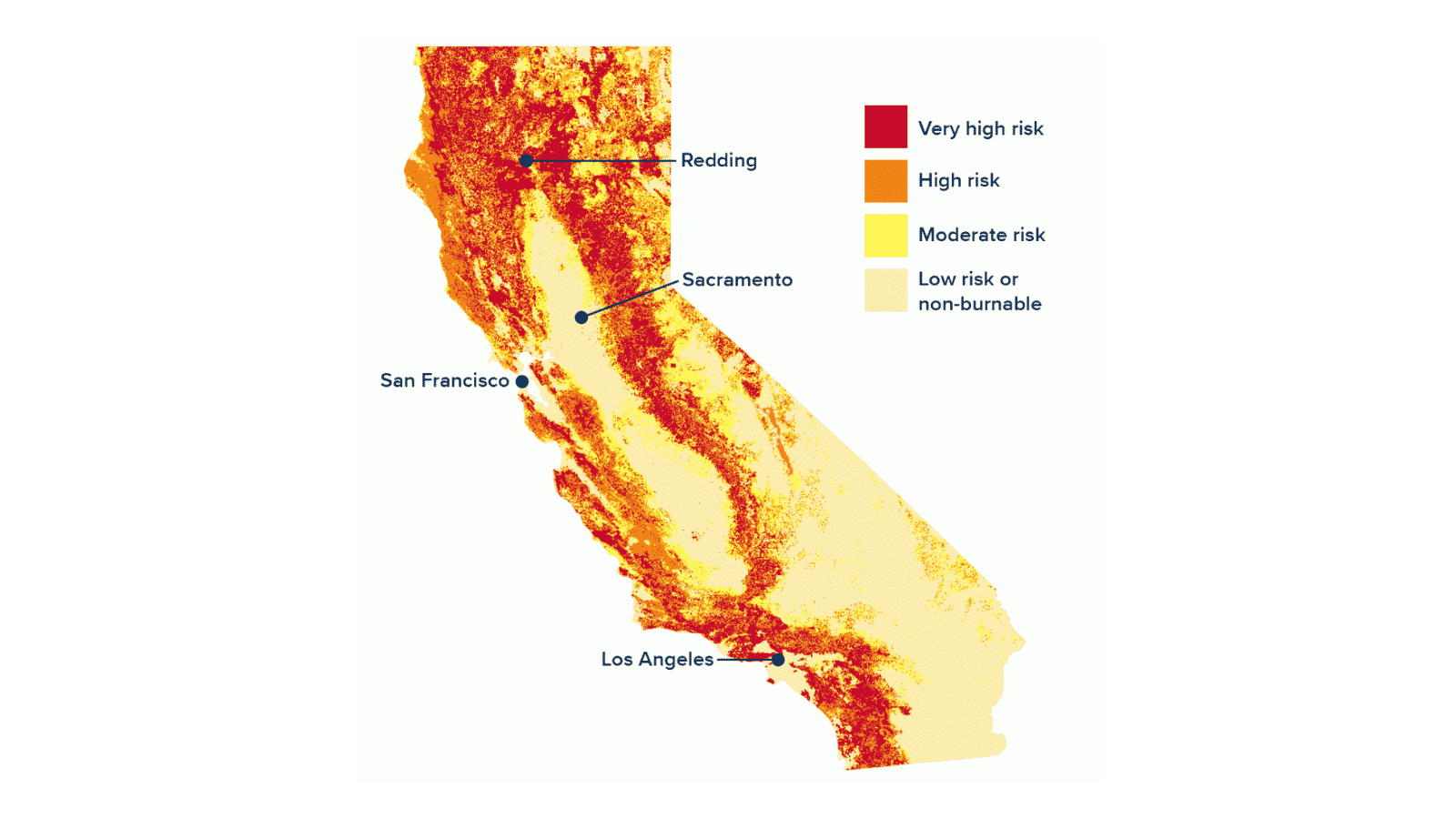

This map illustration, showing the fire risk in California, is drawn from the state’s Fire Hazard Severity Zone map and USDA Forest Service’s Wildfire Hazard Potential map. Credit: Russ Thebaud/UC Davis

As the weather heats up, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CAL FIRE) reminds residents to create an “Ember-Resistant Zone” and prepare their properties for wildfire season with the following recommendations:

- “Use hardscape like gravel, pavers, concrete and other noncombustible materials. No combustible bark or mulch.

- Remove all dead and dying weeds, grass, plants, shrubs, trees, branches, and vegetative debris.

- Limit plants in this area to low growing, nonwoody, properly watered and maintained plants.

- Limit combustible items (outdoor furniture, planters, etc.) on top of decks.

- Replace combustible fencing, gates, and arbors attach to the home with noncombustible alternatives.

- Relocate garbage and recycling bins outside this zone, as well as boats, vehicles, and other combustible items.”

CAL FIRE also offers some tips on “hardening your home” against embers or flying particles, as studies have found that embers were responsible for more than 90% of homes destroyed in wildfires:

- “Block any spaces between your roof covering and sheathing with noncombustible materials (bird stops).

- Install a noncombustible gutter cover to prevent the accumulation of leaves and debris in the gutter.

- Install ember and flame-resistant vents.

- Caulk or plug gaps greater than 1/8-inch in siding and replace any damaged boards, including those with dry rot.

- Upgrade windows to multi-paned, including a minimum of one pane of tempered glass.”

Learn how to prepare your home and property for wildfire

An Old Building Solution, With a Modern Engineering Twist

Developing fire-resistant construction methods and materials is central to addressing climate mitigation and adaptation. Plans to build new developments or rebuild after disasters need to consider issues such as cost, scalability, and structural ability to withstand extreme weather events including hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, and wildfires.

These issues are at the heart of Dr. Michele Barbato’s research. The UC Davis structural engineer and CITRIS Climate faculty director develops innovative approaches and structural solutions to construction materials and methods to cultivate climate resilience. Tackling the issue of building affordable, disaster-proof housing, Barbato and his team at the UC Davis Climate Adaptation Research Center re-discovered an ancient solution—one that’s been around for many thousands of years.

The “old-new” solution? An engineered form of mud—compressed and stabilized by adding cement, limestone, or chemicals into earth blocks. The technique of using natural materials in construction has been around a long time and enables structures to withstand natural events such as earthquakes, storms, and fires. Drawing from the materials and techniques used to build long-lasting structures like the Great Wall of China, Barbato notes that we’re able to create the same kind of resilient, long-lasting structures.

UC Davis graduate student Nitin Kumar mixes a small batch of earth block bricks. Credit: Karin Higgins/UC Davis

Earth block construction isn’t new to California. The adobe missions, which are remarkably energy-efficient thanks to their high thermal mass, are a prime example as they absorb heat and maintain relatively cool indoor temperatures throughout the day. Similarly, Barbato and his team are looking for an economical, eco-friendly way to improve community resilience to the growing threat of wildfires. When reinforced with rebar, the earth blocks—which are fire-, hurricane-, and wind-resistant—have the potential to withstand earthquakes as well.

In an impressive test, Barbato’s students compared the response of wood and earth blocks to extreme heat by using a blowtorch with temperatures of 3400 degrees Fahrenheit—exceeding the level of heat reached by most wildfires. While the wood blocks quickly char and burn, the earth blocks remain largely untouched, with minimal signs of discoloration. The group also heated the earth blocks in a furnace, achieving increasing strength up to roughly 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

A blow torch of 3,400 degrees Fahrenheit blasts a block of wood and an earth block at the same time. The wood block quickly caught flame, while the earth block did not burn. Credit: Karin Higgins/UC Davis

Earth blocks have the potential to be a cost-effective solution—after all, earth is a common and readily available building material. But blocks for building need to be engineered correctly to withstand extreme weather events and other potential stressors. Barbato emphasizes that we don’t have the luxury to keep constructing in the same way—the climate crisis is as urgent as is the need for affordable housing. He warns that current construction methods will need to anticipate the likely impacts of climate change, including projected wind speeds, noting that “if we’re building back better, we need to design not for wind loads or fire loads that are here now but for the ones we think our structures will have to survive in the future.”

While there are many challenges in designing buildings for the future, there are also many opportunities. Earth block construction can be produced on site using local materials, eliminating the need for transportation; this building technique also has heating and cooling advantages. Barbato remains optimistic: not only can the earth blocks help address wildfire risk and climate change, but they have the potential to expand affordable housing as well.

So what’s the catch? To enable the widespread adoption of earth blocks, there needs to be public trust and support. However, there is not yet a lobby to promote the use—and public buy-in—of these materials in the way of steel and concrete. Noting that his research group has been “able to resolve all technical and engineering issues that were encountered along the way,” Barbato remains optimistic, as “the challenge now is achieving acceptance and implementing adoption for these old-new type of structures.”

Feature image: Nitin Kumar, Michele Barbato, Julie Nguyen, and Thomas Tonthat with earth blocks. Credit: Karin Higgins/UC Davis